Time Piece

Starting in mid-1964, Jim Henson began work on a side passion project that again speaks to the fact that puppetry not only wasn’t his only form of artistic expression but perhaps wasn’t even his favorite. And if that’s not necessarily the case, it at least underlines his lifelong desire to pursue other forms of storytelling and film-making. At this point, puppetry paid the bills, and he certainly enjoyed it, but he wanted more. He considered himself more of a visual artist and designer than a puppeteer (and interestingly, his later Muppet departures such as The Dark Crystal and Labyrinth would wed his love for complex worldbuilding through scenic design and art with the most advanced puppetry the world had ever seen), and in this 8-minute-long short film, which he originally called Time to Go before finally settling on Time Piece, he was able to fully indulge that part of himself.

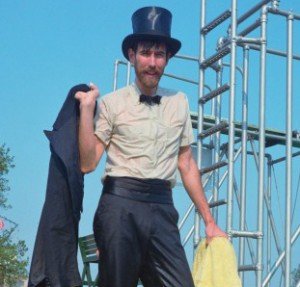

Time Piece is a strange, artsy little film that is essentially about a man who, in Jerry Juhl’s words, was “running from time,” like both the narrator of “Tick Tock Sick,” and Jim himself. Significantly, Jim actually stars in the film as the man being relentlessly harassed by the constant ticking of the clock. As I discussed in the post I just linked to, Jim was always aware that despite his thousands of creative ambitions, he’d only ever be able to complete a small fraction of them, and so he was always working as hard as he could on as much as he could. The fact that he spent almost a year on Time Piece, gradually filming small pieces of the project in between continuing to do his day job, which consisted of The Jimmy Dean Show, commercials, and other TV appearances, speaks to that. Constantly, magically juggling seemingly hundreds of projects across the globe at once would later come to practically define his career.

As with the early Muppets and how Jim was able to see ahead of other puppeteers at the time, realizing that puppets designed for television would have to be different than ones meant for a theatre, and that puppeteers didn’t have to hide behind a stage but simply out of camera range, he saw further than other people in regards to other aspects of filmmaking too. With its very short shots and rapid-fire editing, Time Piece resembles a music video, an art form that didn’t exist yet but would be popular around 2 decades later. It also calls to mind a number of sequences in Jim’s short live-action pieces for Sesame Street.

Again, the entire film is about a man running from time, and in a way, that’s about it. However, Jim conveys this through a practically kaleidoscopic barrage of odd images and weird juxtapositions that are by turns, funny, bizarre, whimsical, and always intriguing. He intended it to be a visual representation of the stream-of-consciousness literary style, and it is definitely that. You can grasp for and even tease out particular moments of meaning but overall the intention is for the viewer to be chaotically bounced around, jarred, and hopefully also amused.

I had seen excerpts of the film in documentaries and museums before, but this is the first time I sat through the entire piece from start to finish, and a number of things really stood out to me. First and foremost is just what a genius Jim Henson was. The fact that, essentially on his free time and on a small budget, he was able to create an assemblage of such striking images and moods, some of which remain so impressive today you practically stop and wonder how he even accomplished them. Or, rather, you would, if you had time to mull any given image over before being instantly tossed into the next insane situation on screen. Jim wrote, starred in, and directed this film, and even composed its rat-a-tat musical score, along with creating the interstitial paper animated sequences, using the same techniques he did for Drums West and Shearing Animation.

And the timing for all the actions in each shot is perfectly timed to the score, which is composed of drum beats and other types of rhythmic noises. The fact that he was able to get each motion on screen and piece of choreography to so exactly match the music alone is an astounding feat. (Even if one weren’t to realize that it’s a film about running from time, it would be difficult to notice how it isn’t about the rhythms of everyday life, each action making its own sort of music, until the fantasy sequences leap into effect and take the film and the protagonist elsewhere.) Jim also was working entirely from storyboards that he drew himself, without a script. The film flows in such a way that it practically feels improvised and yet each moment was painstakingly planned out in advance.

Another thing that surprised me was how funny it is. On the one hand, Jim is clearly indulging in a more artsy, for-lack-of-a-better-word pretentious side than we usually see from him, with a great deal of pop-art-style imagery and deliberately unsubtle, in-your-face symbolism (and with nary a puppet in sight!), but on the other, the film has such a sense of cheerful, weird whimsy and copious tongue-in-cheek self-awareness that it undercuts any sense of performance art self-importance that sometimes mars similar work from other artists. Even those who generally have no interest in this sort of film–cough cough ME cough cough–can find themselves won over by its humor, as well as its jaw-dropping ability to, in shot after shot, show you probably the last thing you might have ever expected.

Pages: 1 2